flowchart TB

A["1 - Identify test cases"] --> B["2 - Get feedback on test cases"]

B --> C["3 - Write one unit test case"]

C --> D["4- Run and watch test fail"]

D --> E["5 - Write just enough code to pass test"]

E --> F["6 - Clean up code"]

F --> G["7 - All tests pass ?"]

G --> |No| C

G --> |Yes| H["Go to next test"]

What is a unit test?

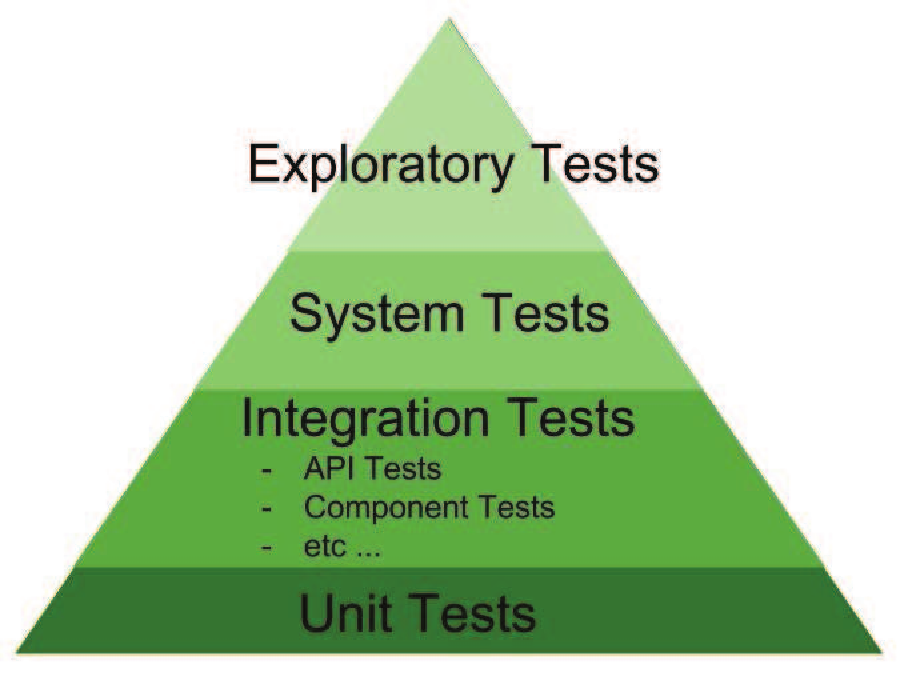

Test levels

There are several types of tests that differ in scope and intention:

- Exploratory Tests

- System Tests

- Integration Tests

- API Tests

- Component Tests

- etc …

- Unit Tests

Unit tests are concerned about the smaller part of a code which are functions and methods.

Besides small, those tests are also cheap to develop and fast to execute since they don’t (or shouldn’t) depend on external or expensive resources.

Unit tests characteristics

Fast

Isolated

Repeatable

Self-verifying

Timely

Unit Tests focus on smallest software block

Below is an example of a unit test.

#include "gtest/gtest.h"

#include "factorial.h"

TEST(FactorialTest, PositiveNumbers) {

EXPECT_EQ(1, Factorial(1));

EXPECT_EQ(2, Factorial(2));

EXPECT_EQ(6, Factorial(3));

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

::testing::InitGoogleTest(&argc, argv);

return RUN_ALL_TESTS();

}How to get started ?

It is important to remember not to write any code yet but instead take a deep breath.

First the TDD workflow should be understood in order to best use unit tests by considering the following steps:

Using TDD to develop a factorial function

A factorial of a number is the product of that number to every other interger less than that.

Mathematical operation is represented with an exclamation mark.

Examples:

0! = 13! = 3 * 2 * 1 = 65! = 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1 = 1207! = 7 * 6 * 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1 = 5040

Results table:

n factorial(n)

---- --------------

0 1

1 1

2 2

3 6

4 24

5 120

6 720

7 5040

8 40320

9 362880

10 3628800

11 39916800

12 479001600

13 6227020800Identify test cases

The first step is to identify test cases and register somewhere such as in a table with a description and the expected behavior.

For a function to calculate factorial of a number, the following test cases can be identified.

| TEST CASE | EXPECTED BEHAVIOR |

|---|---|

| small positive numbers | should calculate factorial |

| nput value is 0 | should return 1 |

Get feedback on test cases

Developers might be tempted to think that they thought about all relevant use cases, but sharing the test cases with others allow to other situations to be captured by a more diverse collection of minds.

After sharing test cases, perhaps other engineers could come up with other test cases.

| TEST CASE | EXPECTED BEHAVIOR |

|---|---|

| small positive numbers | should calculate factorial |

| input value is 0 | should return 1 |

| input value is negative | return error code |

| input value is a bigger positive integer | return overflow error code |

Write one test case as a unit test

Avoid writing multiple test cases, only one test case at a time.

Considering the test case input value is 0, the corresponding test case can be coded as below.

| TEST CASE | EXPECTED BEHAVIOR |

|---|---|

| input value is 0 | should return 1 |

TEST(FactorialTest, FactorialOfZeroShouldBeOne)

{

ASSERT_EQ(1, factorial(0)); // 0! == 1

}Watch test failing

Avoid trying to jump into code to make the test pass, before make sure that the test will fail for the right reasons.

Initially, the test won’t compile unless a factorial function is created.

Focus on only satisfying the compiler by providing an empty factorial C++ function, don’t consider implementation.

When trying to run the test again, the following output will be observed.

[----------] 1 test from FactorialTest

[ RUN ] FactorialTest.FactorialOfZeroShouldBeOne

Actual: -234343253.3253434

Expected: 1

[ FAILED ] FactorialTest.FactorialOfZeroShouldBeOne

[----------] 1 test from FactorialTest (0 ms total)Write just enough code to pass test

In order to pass the test below, consider the minimal implementation possible.

TEST(FactorialTest, FactorialOfZeroShouldBeOne)

{

ASSERT_EQ(1, factorial(0)); // 0! == 1

}To pass the test, the function should only return 1 to make it pass.

int factorial(int n)

{

return 1;

}Clean up code

After test pass and code works, don’t forget to clean up the code and consider the following:

Clean up accumulated mess

Refactorings

Optimizations

Readability

Modularity

Don’t miss this step!

Go to next test

TEST(FactorialTest, FactOfSmallPositiveIntegers)

{

ASSERT_EQ(1, factorial(1));

ASSERT_EQ(24, factorial(4));

ASSERT_EQ(120, factorial(5));

}Google C++ Testing Framework - Basics

The TDD workflow above can be applied to any unit test framework but to develop C++ code, Google C++ Testing Framework provides the following benefits:

Portable: Works for Windows, Linux and Mac

Familiar: Similar to other xUnit frameworks (JUnit, PyUnit, etc.)

Simple: Unit tests are small and easy to read

Popular: Many users and available documentation

Powerful: Allows advanced configuration if needed

Tests

In Google Test, TEST ( ) macro defines a test name and function.

TEST(test_case_name, test_name)

{

... test body ...

}Example:

TEST(FibonacciTest, CalculateSeedValues)

{

ASSERT_EQ(0, Fibonacci(0) );

ASSERT_EQ(1, Fibonacci(1) );

}Assertions

Assertions are used to check for expected behavior from a function or method.

Google tests supports the following types of assertion:

ASSERT_* fatal failures (test is interrupted)

EXPECT_* non-fatal failures

The error message from those assertions can be customised by using the operator << followed by a custom failure message.

ASSERT_EQ(x.size(), y.size()) <<

"Vectors x and y are of unequal length";

for (int i = 0; i < x.size(); ++i)

{

EXPECT_EQ(x[i], y[i]) <<

"Vectors x and y differ at index " << i;

}There are assertions available for different situations involving booleansm, numbers, string, etc as it can be seen below:

Logic assertions

| Description | Fatal assertion | Non-fatal assertion |

|---|---|---|

| True condition | ASSERT_TRUE(condition); | EXPECT_TRUE(condition); |

| False condition | ASSERT_FALSE(condition); | EXPECT_FALSE(condition); |

Integer assertions

| Description | Fatal assertion | Non-fatal assertion |

|---|---|---|

| Equal | ASSERT_EQ(expected, actual); | EXPECT_EQ(expected, actual); |

| Less then | ASSERT_LT(expected, actual); | EXPECT_LT(expected, actual); |

| Less or equal then | ASSERT_LE(expected, actual); | EXPECT_LE(expected, actual); |

| Greater then | ASSERT_GT(expected, actual); | EXPECT_GT(expected, actual); |

| Greater or equal then | ASSERT_GE(expected, actual); | EXPECT_GE(expected, actual); |

String assertions

| Description | Fatal assertion | Non-fatal assertion |

|---|---|---|

| Different content | ASSERT_STRNE(exp, actual); | EXPECT_STREQ(exp, actual); |

| Same content, ignoring case | ASSERT_STRCASEEQ(exp,actual); | EXPECT_STRCASEEQ(exp,actual); |

| Different content, ignoring case | ASSERT_STRCASENE(exp,actual); | EXPECT_STRCASEEQ(exp,actual); |

Explicit assertions

| Description | Assertion |

|---|---|

| Explicit success | SUCCEED(); |

| Explicit fatal failure | FAIL(); |

| Explicit non-fatal failure | ADD_FAILURE(); |

| Explicit non-fatal failure with detailed message | ADD_FAILURE_AT("file_path", line_number); |

Exception assertions

| Description | Fatal assertion | Non-fatal assertion |

|---|---|---|

| Exception type was thrown | ASSERT_THROW(statement, exception); | EXPECT_THROW(statement, exception); |

| Any exception was thrown | ASSERT_ANY_THROW(statement); | EXPECT_ANY_THROW(statement); |

| No exception thrown | ASSERT_NO_THROW(statement); | EXPECT_NO_THROW(statement); |

Floating point number assertions

| Description | Fatal assertion | Non-fatal assertion |

|---|---|---|

| Double comparison | ASSERT_DOUBLE_EQ(expected, actual); | EXPECT_DOUBLE_EQ(expected, actual); |

| Float comparison | ASSERT_FLOAT_EQ(expected, actual); | EXPECT_FLOAT_EQ(expected, actual); |

| Float point comparison with margin of error | ASSERT_NEAR(val1, val2, abs_error); | EXPECT_NEAR(val1, val2, abs_error); |

Test fixtures

Test fixtures are tests that operate on shared data and those are also supported by this test framework.

Each test fixture should declared as a class with methods SetUp to inicialize variables before all tests and TearDown after all tests. Auxiliary methods can also be declared if necessary.

class LogTests : public ::testing::Test {

protected:

void SetUp() {...} // Prepare data for each test

void TearDown() {...} // Release data for each test

int auxMethod(...) {...}

}In Separate, the test cases can be declared with TEST_F macros.

TEST_F(LogTests,cleanLogFiles) {

... test body ...

}Controlling execution

- Run all tests

mytestprogram.exe- Runs "SoundTest" test cases

mytestprogram.exe -gtest_filter=SoundTest.*- Runs tests whose name contains "Null" or "Constructor"

mytestprogram.exe -gtest_filter=*Null*:*Constructor*- Runs tests except those whose preffix is "DeathTest"

mytestprogram.exe -gtest_filter=-*DeathTest.*- Run "FooTest" test cases except "testCase3"

mytestprogram.exe -gtest_filter=FooTest.*-FooTest.testCase3Temporarily Disabling Tests

In order to disable test cases, just add DISABLED preffix before the test case name:

TEST(SoundTest,DISABLED_legacyProcedure) { ... }To disable all tests cases inside a test fixture, add DISABLED to the fixture test class name:

class DISABLED_VectTest : public ::testing::Test

{ ... };

TEST_F(DISABLED_ArrayTest, testCase4) { ... }However it is still possible to run all tests including disabled tests:

mytest.exe --gtest_also_run_disabled_testsExecution customization

Junit Output format

The output of the testing program can be redirected as an xml compatible to JUnit and this is specially useful for automated building tools such as Jenkins.

To do so, just add parameter --gtest_output .

mytest_program.exe --gtest_output ="xml:directory/myfile.xml"The output XML format (JUnit compatible) looks like this:

<testsuites name="AllTests" ...>

<testsuite name="test_case_name" ...>

<testcase name="test_name" ...>

<failure message="..."/>

<failure message="..."/>

<failure message="..."/>

</testcase>

</testsuite>

</testsuites>Listing test names (without executing them)

It is also possible just to list the test case names without executing them by adding the parameter --gtest_list_tests .

mytest_program.exe --gtest_list_testsTestCase1.

TestName1

TestName2

TestCase2.

TestNameMake code testable

Types of functions

Testing functions

Functions and methods can be designed and developed in different ways but from testing perspective, there are essentially 3 types of functions:

functions with input and output. (typically math functions)

Ex:result = factorial(n)functions with input and object side-effect.

Ex:person.setName('John');functions with input and not testable side-effect.

Ex:drawLine(30,30,120,190);

Functions with input and output

the easiest case - direct implementation

functions should be refactored to this format when possible

TEST(FibonacciTest, FibonacciOfZeroShouldBeZero) {

ASSERT_EQ(0, fibonacci(0));

}

TEST(FibonacciTest, FibonacciOfOneShouldBeOne) {

ASSERT_EQ(1, fibonacci(1));

}

TEST(FibonacciTest, FibonacciOfSmallPositiveIntegers) {

ASSERT_EQ(2, fibonacci(3));

ASSERT_EQ(3, fibonacci(4));

}Functions with input and object side-effect

not so direct but still easy

object should contain a read method to check state

TEST(PersonTest, SetNameShouldModifyName) {

Person p;

p.setName("James");

ASSERT_STR_EQ("James", p.getName());

}Functions with input and not testable side-effect

can´t test what we can’t measure (in code)

not worth effort for unit testing

TEST(DisplayTest, LineShouldBeDisplayed)

Display display;

display.drawLine(20,34,100,250);

??????????? - How to assert this ???

}Configuration vs Implementation

Testing C++ code can get complicated if not impossible when different aspects such as configuration and logic are mixed in the same code block.

Isolate configuration from the actual code

Consider the following example below.

How to test Init failure in this code ?

class Component {

public:

int init() {

if (XYZ_License("key_abcdefg") != 0) {

return INIT_FAILURE;

}

return INIT_SUCCESS;

}

};The problem is that 'init' is a function without testable side-effects. How to fix this ?

In order to make the code testable, instead separate configuration from code.

class Component

{

protected:

std::string license = "key_abcdefg"; // configuration

public:

int init() {

if (XYZ_License(license) == FAILURE)

{

return INIT_FAILURE;

}

}

};Note that, in the code above, the license information became an object variable with protected permission.

Next step, is to extend C++ class to add methods to access protected information.

class TestableComponent : public Component

{

public:

void setLicense(string license) {

this.license = license;

}

};Adding method 'setLicense' is necessary to modify the state of 'init' method.

Isolate configuration from the actual code

Given the testable component above, it is now possible to write a proper test:

TEST(ComponentTest, UponInitializationFailureShouldReturnErrorCode)

{

// Auxiliar testing class can be declared only

// in the scope of the test

class TestableComponent : public Component

{

public:

void setLicense(string license) {

this.license = license;

}

};

TestableComponent component;

component.setLicense("FAKE_LICENSE");

ASSERT_EQ(INIT_FAILURE, component.init());

};Make code testable with application code

Besides configuration and logic, consider to extract out pure application or domain logic in separate functions or methods.

Isolate these logic from other aspects such as presentation whose feedback or side-effect is measured visually instead of programatically.

Separate application logic from presentation

There are some reasons from isolating UI or presentation layer from application logic:

Presentation logic refers to UI components to show user feedback

Application logic refers to data transformation upon user or other system input

Presentation and logic should be separated concerns

Presentation is usually not unit testable

Application logic is usually testable

As an example, conside the code block below that mixed both concerns:

std::string name = txtName.text().string(); // txtName is a UI component

std::size_t position = name.find(" ");

std::string firstName = name.substr(0, position);

std::string lastName = name.substr(position);

lbDescription.text().setString(lastName + ", "+ firstName);In order to make code testable, the application logic should be extracted out from the presentation layer.

How to test code below if presentation and application logic are mixed ?

std::string name = txtName.text().string(); // txtName is a UI component

std::string description = app.generateDescription(name);

lbDescription.text().setString(description);TEST(ApplicationTest, shouldMakeDescription) {

Application app;

std::string description;

description = app.makeDescription("James Oliver");

ASSERT_STREQ("Oliver, James", description);

}External dependencies

Code with mixed responsiblities

External dependencies is the part that is not controlled but only requested by the software such as HTTP requests, database connection, etc.

Below is an example of code that mixes logic with HTTP requests to an external resource.

How to test this ?

HttpResponse response;

response = http.get("http://domain/api/contry_code?token=" + token);

std::string countryCode = response.body;

std::string langCode;

if (countryCode == BRAZIL) {

langCode = PORTUGUESE;

} else if (countryCode == USA) {

langCode = ENGLISH;

} else {

langCode = ENGLISH;

}

ui.setLanguage(langCode);Identify and isolate dependency

The first step is to identify and isolate those external dependencies.

In this example, the external resource is an HTTP request which was replaced by an interface defined in the class WebAPIGateway while the language support is handled by the LanguageHelper .

WebAPIGateway webAPI;

std::string countryCode=webAPI.userCountryCode(token);

LanguageHelper language;

std::string langCode=language.findLang(countryCode);

ui.setLanguage(langCode);With that, it is now possible to test each component separately.

Below it is possible to see how the LanguageHelper can be tested.

TEST(LanguageHelperTest, shouldFindLanguageForCountry)

{

LanguageHelper language;

ASSERT_EQ(PORTUGUESE, language.findLang(BRAZIL));

ASSERT_EQ(ENGLISH, language.findLang(USA));

ASSERT_EQ(ENGLISH, language.findLang(JAPAN));

...

}Fake objects

Another technique to test objects is to make use og Google Mock. With that library, a fake version of the external resource interface can be created as a way to skip this dependency and test the logic when trying to use it.

#include "gmock/gmock.h"

TEST(WebAPIGatewayTest, shouldFindUserCountry){

class HttpRequestFake : public HttpRequest

{

std::string userCountryCode(std::string token){

std::string country = "";

if (token=="abc") country = BRAZIL;

return country;

}

};

HttpRequest* httpFake = new HttpRequestFake();

WebAPIGateway api = WebAPIGateway(httpFake);

std::string countryCode = api.userCountryCode("abc");

delete httpFake;

ASSERT_EQ(BRAZIL, countryCode);

}Mock objects

A mock object is not only concerned about returning a fale controlled value like above but also it quantifies how many and what parameters were used to call the mocked method.

#include "gmock/gmock.h"

class HttpRequestMock : public HttpRequest

{

MOCK_CONST_METHOD1(get(), std::string(std::string));

};

TEST(WebAPIGatewayTest, shouldFindUserCountry){

HttpRequest* httpMock = new HttpRequestMock();

WebAPIGateway api = WebAPIGateway(httpMock);

EXPECT_CALL(httpMock,

get("http://domain/api/contry_code?token=abc")

.Times(1)

.WillOnce(Return(Response(BRAZIL)));

std::string countryCode = api.userCountryCode("abc");

delete httpMock;

ASSERT_EQ(BRAZIL, countryCode);

}Code with dependencies

Some types of situations are not testable due to the lack of measurable side-effects.

That is the case for visualization, for instance, the code needs to be executed and observed to check if it looks correct like in the example below with OpenGL.

void drawQuad(float cx, float cy, float side)

{

float halfSide = side / 2.0;

glBegin(GL_LINE_LOOP);

glVertex3f(cx-halfSide, cy-halfSide);

glVertex3f(cx+halfSide, cy-halfSide);

glVertex3f(cx+halfSide, cy+halfSide);

glVertex3f(cx-halfSide, cy+halfSide);

glEnd();

}Identify and isolate dependency

To address that, the logic that describes the geometry should be extracted out from the library-specific presentation function calls.

The presentation layer is isolated with an interface IDisplay that acts, in this case, as a dependency injection.

void drawQuad(float cx, float cy, float side, IDisplay* display {

float halfSide = side / 2.0;

std::vector<float> vertices = {

cx-halfSide, cy-halfSide,

cx+halfSide, cy-halfSide,

cx+halfSide, cy+halfSide,

cx-halfSide, cy+halfSide

};

display->rectangle(vertices);

}

class Display : public IDisplay {

public: void rectangle(std::vector<float> vertices) {

glBegin(GL_LINE_LOOP);

glVertex3f(vertices[0], vertices[1]);

...

glEnd();

}

};Fake objects

Another example where a fake display object is used to check vertices calculations without display.

TEST(DrawTests,drawQuadShouldCalculateVertices){

class FakeDisplay : public Display {

protected: std::vector<float> _vertices;

public:

void rectangle(std::vector<float> vertices) {

_vertices = vertices;

}

std::vector<float> vertices() {

return _vertices;

}

};

IDisplay* display = new FakeDisplay();

drawQuad(10.0, 10.0, 10.0, display);

ASSERT_VECT_EQ({5.0, 5.0, 15.0, 5.0, 15.0, 15.0, 5.0, 15.0}, display->vertices());

}Mock objects

As for mocks, the same can be achieved with the advantage of counting the method call and arguments being passed.

#include "gmock/gmock.h"

TEST(DrawTests,drawQuadShouldCalculateVertices) {

class MockDisplay : public Display {

MOCK_METHOD1(rectangle, void (std::vector<float>);

};

IDisplay* display = new MockDisplay();

EXPECT_CALL(

display,

rectangle({ 5.0, 5.0, 15.0, 5.0, 15.0, 15.0, 5.0, 15.0 }))

.Times(1);

drawQuad(10.0, 10.0, 10.0, display);

}General recommendations

Test behavior not implementation

There is no behavior in non-public methods

Use name convention for tests to improve readability

Test code should be as good as production code - it is not sketch code

GTest alone can’t help you

Workflow is important - talk to your QA

Improve modularization to avoid being trapped by non testable code

Use mock objects with caution

Understand the difference between fake and mock objects

References

Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship

Robert C. Martin - Prentice Hall PTR, 2009